The Investor July 2022

ShareFinder’s prediction for Wall Street for the next 12 months:

Beating Capital Gains Tax

By Richard Cluver

Arguably the most irksome problem facing the average long-term investor is Capital Gains Taxation because it blocks one from making urgently-needed portfolio adjustments which could prove very costly in the long run.

Since it is a tax that almost entirely arises because of Government mishandling of the economy, it should surprise nobody that more than half our taxpayers have disappeared over the past five years! Is it a tax revolt or is one of South Africa’s most valuable resources, our entrepreneurial class, quitting our shores?

CGT is, of course, a favourite of left-leaning politicians since it allows them to demonstrate to an increasingly critical electorate that the State is taking from the Rich to give to the Poor. But for an ever-shrinking tax base it is a very emotive issue in South Africa given that one only needs assets of R2.7-million to be numbered among the top one percent….the folk who provide the Government with most of its tax income!

Since, furthermore, there were only 61 000 one percenters in the country compared with an adult population of 35.434-million, their votes do not count for much which probably explains why they are emigrating in droves in order to escape our comparatively punitive tax system, a collapsing currency which is threatening their ability to hang onto their wealth and ever-growing political risk. Collectively, this tiny group annually hands over to the government some 25.9 percent of the country’s TOTAL GDP, making us one of the top ten most highly taxed nations on earth.

Worse, polls make it clear that most South Africans now believe that political fat cats are siphoning off large amounts of their taxes through corruption. For a political class more interested in the contents of the latest Mercedes Benz catalogue than the needs of their constituents, the increasing lack of accountability of the majority of our municipalities and the collapse of everything from electricity to road and rail services to potholed roads and dried-up household water supplies, all clearly illustrate to the electorate that the Government has neither the will nor the ability to stop the rot. So it should surprise nobody that our tax base is shrinking rapidly.

Furthermore the alarm bells are ringing loudly signalling that a tax revolt is in progress. A new study by Hanneke du Preez, Associate Professor at the Pretoria University Department of Taxation and associate lecturer Keamogetswe Molebalwa has found that all five of the major contributory factors underlying the greatest tax revolts in recorded history, are present in South Africa today. The five which led to the Jewish Revolt of 66 AD-70 AD, the Great Spanish Revolt of 1520-1521 and the Proposition 13 Californian Revolt of 1978 were systematically identified as high unemployment, high indebtedness, inequality, high inflation and an excessive tax burden.

Currently taxpayers are voting with their feet. According to Jean du Toit, Head of Tax at Tax Consulting SA, the three upper income bands of taxpayers whose taxes account for 94 percent of government income have declined in numbers from 6.1-million taxpayers to a current 2.7-million representing a 55.73 percent reduction over the past five years.

And of all the taxes that upper-income South Africans have to pay, Capital Gains is probably the most irksome since the greater part of the asset gains on which investors are taxed are the consequence of inflation which is, in turn, almost entirely attributable to Government’s mishandling of the economy.

There are accordingly quite powerful moral arguments for and against CGT and, since it is reportedly very expensive and difficult to collect which, from the fiscus point of view makes it a very marginal exercise, it should not surprise anyone that there is a powerful international lobby pressing for it to be scrapped.

Nevertheless, while we are forced to live with it, it might surprise its most ardent critics that for South African investors there is a way around the tax which serves to bring the legislation closer in line with practice in more progressive countries which these days only levy CGT when one finally cashes in one’s investments.

In terms of section 42 of the South African Income Tax Act, if an investor disposes of an asset to a company or a collective investment scheme in exchange for an equity share such as, for example a unit issued by a unit trust, at an amount equal to the base cost of that asset, there will be no capital gain to the investor as the proceeds will equal the base cost.

To offer a practical example, part of the reason that my Prospects Portfolio achieved the enviable status as the global best performer for the decade to December 2021 was that it included shares in Naspers which I bought in March 2011 for R357.14 a share which by January 2021 had risen eleven fold in value to R3 888 a share.

Writing in the Prospects newsletter at that time I expressed concern that the shares had become very overpriced and pointed to the fact that investors worldwide were beginning to voice growing concern about the precarious pyramid structure via which Naspers owned its principal asset, the Chinese tech company Tencent which, people feared, could be instantly unwound if the Chinese authorities took action to enforce their fundamental belief that only Chinese citizens could own shares in domestic companies. I accordingly took the, unpopular action of selling a third of the portfolio’s Naspers holdings at R3 367.26 which, considering the fact that by May this year the shares had fallen to a low of R1 421.74, proved to be an inspired move.

Recently, the shares began a remarkable recovery following the news that Naspers had decided to progressively sell off Tencent shares until such time as the long-existing sum of the parts value discount of over 50 percent was ended. The decision has caused a consensus of fund managers to calculate that the shares should climb to R2 690.21 which, given a recent peak of R2 612.33 (July 5) implies that a new decision point is close.

The green trend line in my graph below suggests that if the long-term trend of Naspers price gains were to return, a price of around R3 800 might be attainable while ShareFinder’s artificial intelligence system suggests that by hanging on until next April a figure of R3 220 is attainable.

To hold on or to sell will, accordingly be a decision that most investors face in the comparatively short-term. So the opinion of a growing body of analysts that Naspers has lost its magic, must weigh upon investors.

To hold on or to sell will, accordingly be a decision that most investors face in the comparatively short-term. So the opinion of a growing body of analysts that Naspers has lost its magic, must weigh upon investors.

At its current price, Naspers is standing at an extremely modest dividend yield of just 0.26 percent. Its former attraction was that over the 20 years to February 2021 it was increasing in value annually by a market record compound average of 37.8 percent meaning that it offered a “Total Return” of 38.06 percent. Unfortunately, since then it was falling at an annualised minus 55.5 percent until early May and, even if you factor in the increases of the past month, that figure remains negative at minus 23.5 percent. Against that, the dividend yield of 0.26 percent makes absolutely no impact upon the Total Return.

Behind those figures is a story of Naspers’s many ventures into a multitude of projects, largely in the food delivery and classified advertisements businesses, which have largely failed to thus far achieve the economies of scale that would make them the kind of international money-spinners which Tencent proved to be. Accordingly, considering that the Total Return of all JSE Blue Chips is currently standing at a positive 11.93 percent, many investors might be very glad to swop their holdings for alternative investments were it not for the fact that by selling they fear they would oblige themselves to pay over a considerable portion of their gains to the tax man.

Well hope is at hand because most Unit Trust managers are prepared to accept parcels of shares in exchange for units at their current face value. Furthermore you can cherry pick the shares you wish to swap so as to rid yourself only of those with a high CGT ticket. You might thus be able to choose to put all or part of the capital so released into a world market tracker or into a local equity tracker.

The best I found was the Old Mutual Global Equity R fund which over the past ten years has delivered 15.5 percent compound and an Investec fund yielding compound annual average growth of 14.5 percent annually over the past five years which are somewhat short of the 18.5 percent annually (together with a 2 percent dividend) achieved by those readers who have elected to copy my Prospects Portfolio month by month over the past decade.

But Prospects Portfolio owners also have the problem that 78 percent of its holdings have achieved significant capital gains and so such investors might be feeling somewhat claustrophobic because of the CGT problem. By swapping their assets at this stage they could thus achieve the diversification they need.

Furthermore by utilising that portion of their unit trust dividend income that exceeds their living needs, augmented by selling just enough units annually to keep within the limits of the R157 900 tax-free income allowance of each beneficiary, they could begin to build a new high-growth portfolio. Given the security of a steadily-yielding unit trust portfolio covering their living needs, such investors could afford risks they might never otherwise be able to take in order to invest in speculative high-growth shares.

It’s a win-win possibility which I am personally following.

Falling From Grace

By Jeff Thomas

“Empires fall from grace with alarming speed.” Every now and then, you receive a comment that, although it may have been stated casually, has a lasting effect, as it offers uncommon insight. For me, this was one of those and it’s one that I’ve kept handy at my desk since that time, as a reminder.

I’m from a British family, one that left the UK just as the British Empire was about to begin its decline. They expatriated to the “New World” to seek promise for the future.

As I’ve spent most of my life centred in a British colony – the Cayman Islands – I’ve had the opportunity to observe many British contract professionals who left the UK seeking advancement, which they almost invariably find in Cayman. Curiously, though, most returned to the UK after a contract or two, in the belief that the UK would bounce back from its decline, and they wanted to be on board when Britain “came back.”

This, of course, never happened. The US replaced the UK as the world’s foremost empire, and although the UK has had its ups and downs over the ensuing decades, it hasn’t returned to its former glory. And it never will.

If we observe the empires of the world that have existed over the millennia, we see a consistent history of collapse without renewal. Whether we’re looking at the Roman Empire, the Ottoman Empire, the Spanish Empire, or any other that’s existed at one time, history is remarkably consistent: The decline and fall of any empire never reverses itself; nor does the empire return, once it’s fallen.

But of what importance is this to us today?

Well, today, the US is the world’s undisputed leading empire and most Americans would agree that, whilst it’s going through a bad patch, it will bounce back and might even be better than ever.

Not so, I’m afraid. All empires follow the same cycle. They begin with a population that has a strong work ethic and is self-reliant. Those people organize to form a nation of great strength, based upon high productivity.

This leads to expansion, generally based upon world trade. At some point, this gives rise to leaders who seek, not to work in partnership with other nations, but to dominate them, and of course, this is when a great nation becomes an empire. The US began this stage under the flamboyant and aggressive Teddy Roosevelt.

The twentieth century was the American century and the US went from victory to victory, expanding its power.

But the decline began in the 1960s, when the US started to pursue unwinnable wars, began the destruction of its currency and began to expand its government into an all-powerful body.

Still, this process tends to be protracted and the overall decline often takes decades.

So, how does that square with the quote, “Empires fall from grace with alarming speed”?

Well, the preparation for the fall can often be seen for a generation or more, but the actual fall tends to occur quite rapidly. What happens is very similar to what happens with a schoolyard bully.

The bully has a slow rise, based upon his strength and aggressive tendency. After a number of successful fights, he becomes first revered, then feared. He then takes on several toadies who lack his abilities but want some of the spoils, so they do his bidding, acting in a threatening manner to other schoolboys.

The bully then becomes hated. No one tells him so, but the other kids secretly dream of his defeat, hopefully in a shameful manner.

Then, at some point, some boy who has a measure of strength and the requisite determination has had enough and takes on the bully.

If he defeats him, a curious thing happens. The toadies suddenly realise that the jig is up and they head for the hills, knowing that their source of power is gone.

Also, once the defeated bully is down, all the anger, fear and hatred that his schoolmates felt for him come out, and they take great pleasure in his defeat.

Also, once the defeated bully is down, all the anger, fear and hatred that his schoolmates felt for him come out, and they take great pleasure in his defeat.

And this, in a nutshell, is what happens with empires.

A nation that comes to the rescue in times of genuine need (such as the two World Wars) is revered. But once that nation morphs into a bully that uses any excuse to invade countries such as Afghanistan, Libya, Iraq and Syria, its allies may continue to bow to it but secretly fear it and wish that it could be taken down a peg.

When the empire then starts looking around for other nations to bully, such as Iran and Venezuela, its allies again say nothing but react with fear when they see the John Boltons and Mike Pompeos beating the war drums and making reckless comments.

At present, the US is focusing primarily on economic warfare, but if this fails to get the world to bend to its dominance, the US has repeatedly warned, regarding possible military aggression, that “no option is off the table.”

The US has reached the classic stage when it has become a reckless bully, and its support structure of allies has begun to de-couple as a result.

At the same time that allies begin to pull back and make other plans for their future, those citizens within the empire who tend to be the creators of prosperity also begin to seek greener pastures.

History has seen this happen countless times. The “brain drain” occurs, in which the best and most productive begin to look elsewhere for their future. Just as the most productive Europeans crossed the Pond to colonise the US when it was a new, promising country, their present-day counterparts have begun moving offshore.

The US is presently in a state of suspended animation. It still appears to be a major force, but its buttresses are quietly disappearing. At some point in the near future, it’s likely that the US government will overplay its hand and aggress against a foe that either is stronger or has alliances that, collectively, make it stronger.

The US will be entering into warfare at a time when it’s broke, and this will become apparent suddenly and dramatically. The final decline will occur with alarming speed.

When this happens, the majority of Americans will hope in vain for a reverse of events. They’ll be inclined to hope that, if they collectively say, “Whoops, we goofed,” the world will be forgiving, returning them to their former glory.

But historically, this never occurs. Empires fall with alarming speed, because the support systems that made them possible have decamped and have become reinvigorated elsewhere.

Rather than mourn the loss of empire that’s on the horizon, we’d be better served if we focus instead on those parts of the world that are likely to benefit from this inevitability.

May I say I told you so?

By Brian Kantor

We like to think that evidence changes beliefs. The problem with beliefs or rather opinions about economic life is that the economy never stands still to conduct experiments with.

We like to think that evidence changes beliefs. The problem with beliefs or rather opinions about economic life is that the economy never stands still to conduct experiments with.

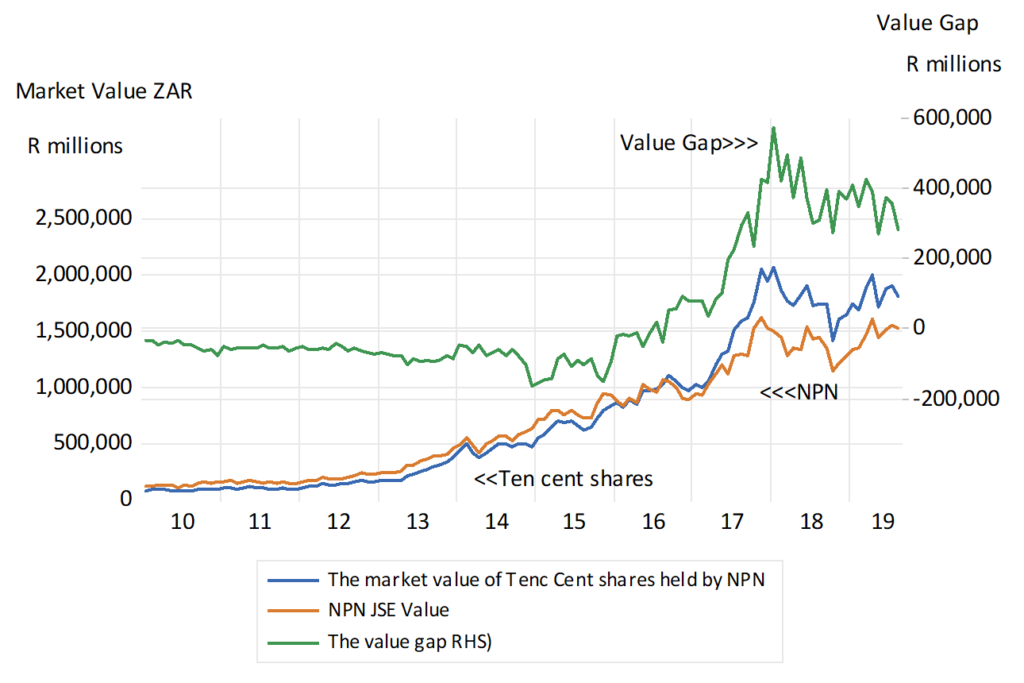

The management of Naspers conducted an experiment in September 2019 to reduce the huge gap between the value of the assets on its books, its Net Asset Value (NAV) or sum of its parts, mostly in the form of its enormously valuable shareholding in Tencent a fabulously successful internet company listed in Hong Kong, and the market value of its shares listed on the JSE.

The board and its management have seemingly learned a great deal from the expensive experiment – unexpectedly so surely – because restructuring its shareholding, establishing a subsidiary company in Amsterdam Prosus (PRX) to hold its Tencent shares and other offshore investments went so badly. The value gap, the difference between the NAV and Market Value (MV) of both NPN and PRX rather than narrow had widened significantly after 2019 despite or rather in small part because of the restructuring. By early June 2022 the discount for NPN (NAV- MV)/NAV)*100 was of the order of 62% and 51% for PRX

Such new awareness has been received with great appreciation and delight of its shareholders these past few weeks. As a result of its change of mind, in the form of a mea-culpa about past actions and the much more tangible decision to sell as much as 2% a year of its holding in Tencent shares, worth potentially USD 10 billion a year, and to return the cash realized to shareholders buying back its shares.

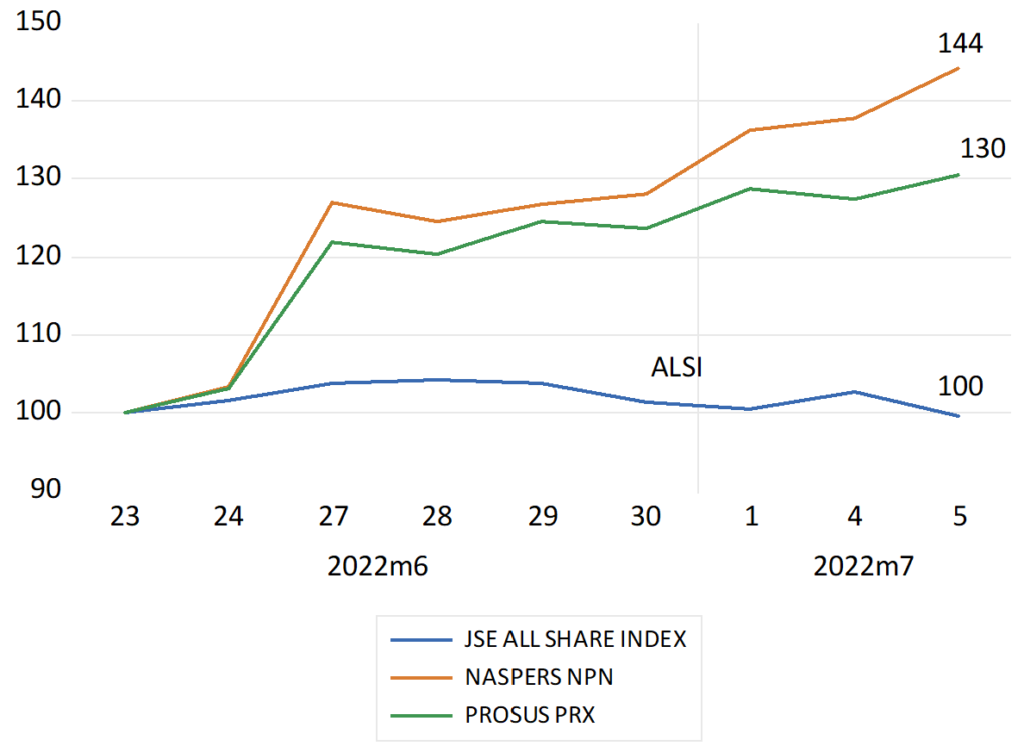

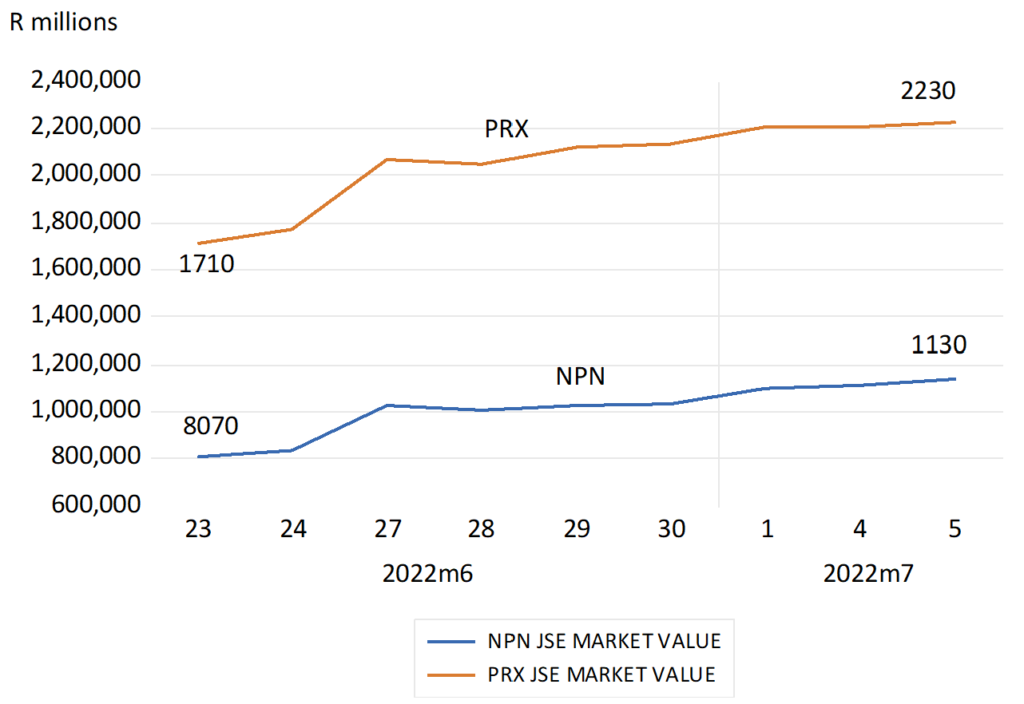

Since the announcement of June 23rd, shareholders in NPN have seen their shares appreciate by 34% adding 323 billion rands to its market value by July 5th while shares in the associate company Prosus (PRX) are up by 26% worth a extra R520 billion rand and the discount has substantially narrowed to the 30% range for PRX and 40% for NPN. A further decision to include success in narrowing the value gap as a key management performance indicator was also helpful. All achieved in days while the JSE has moved sideways.

Daily share price moves and the JSE All Share Index June 23rd – July 5th (June 23rd=100)

Source:Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

Market Value; Naspers and Prosus, Rand millions

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

Naspers and the Value Gap 2010 – 2019 Month end data.

Source; Bloomberg and Investec Wealth and Investment

The Naspers board had been of the view that it was the South African and JSE connections, higher SA risk premiums and a limited shareholding opportunity in SA, where NPN featured so largely, stood in the way of their receiving proper recognition for their vigorous efforts in diversifying their balance sheets. Hence the restructuring. My opinion, long shared with whoever might read or listen to them, was that the difference between the market value of the sum of parts of any investment holding company and its share market value including NPN and PRX could be largely attributed to three factors. And that where a company was domiciled or listed would be of minor consequence.

Firstly that the reported value of unlisted subsidiary companies could be over-estimated to exaggerate NAV. Secondly that the estimated future costs of maintain a head office, including the employment benefits (including share options and issues) expected to be realized to senior management would be present valued to reduce the market value of the holding company shares. Managers can prove very expensive stakeholders.

And thirdly and most importantly would be the investors or potential investors estimate of the present value of the investment programme of the holding company. They might well judge and expect that the future value of the investments and acquisitions to be made by the Holding Company will be worth less, perhaps much less, than they will cost shareholders in cash or returns foregone. And the more investments undertaken the more value destruction and the lower the value of the shares in the holding company priced lower to promise a market related return for shareholders. If such were the market view the less cash invested, the more returned to shareholders by way of dividends, share buy backs or via the unbundling of mature investments, the more value created for shareholders. Naspers/Prosus is helping to prove my theory.

Follow for examples these BD links https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/companies/2020-09-14-watch-is-nasperss-management-destroying-its-value/

No Soft landings

By John Mauldin

“There’s no soft landing when you’re this far out of equilibrium.”

—Tom Hoenig

My recent letters featured highlights from our Strategic Investment Conference. I told you they would build toward a conclusion that might not be obvious. Today we’ll lift that final curtain.

My recent letters featured highlights from our Strategic Investment Conference. I told you they would build toward a conclusion that might not be obvious. Today we’ll lift that final curtain.

Some of it is good news. Innovation will continue, technology will evolve, living standards will improve in many ways as the 2020s unfold. We had several sessions focused on technology and the future, which I have not written about. Positive things will happen in the background but our attention will be on a less pleasant foreground. News media rarely headline the amazing new technologies that will improve our lives. They focus on the negatives and crisis because that is what we humans read and they get paid by the number of clicks. Sad but true.

In the final panel we talked about what’s coming. No surprise, much depends on what the Federal Reserve and other central banks do. Trying to control the inflation that arose from their own past choices, they will try to tighten policy without going too far. Their history of making such “soft landings” is not impressive.

But the challenge is more than monetary. Fiscal authorities (legislatures and governmental authorities) had a hand in creating all this, too, and they must be part of any solution. Their history isn’t reassuring, either.

I have written before that we’ve reached a point where all the options are bad, but some are worse than others. People talk about the Fed scoring an economic “soft landing,” tightening just enough to control inflation, but not setting off a deep recession.

That would be nice. The chance that all the necessary pieces will line up that way? Somewhere between slim and none, and as my dad used to say, “Slim left town.” And while my memory isn’t perfect, I don’t believe any speaker at the conference believed in the possibility of a soft landing. And even if we get one, we have serious problems that predate this inflation. They haven’t gone anywhere.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s see what the SIC experts predict.

Start/Stop

I like to say conferences are my personal art form. I enjoy finding the right mix of speakers and arranging them into a thought-provoking agenda. The SIC closing panel is my artwork’s final touch. I assemble a “dream team” with different perspectives, not knowing exactly where it will go. Then I add a moderator and myself so someone can light the fuse. It’s always a fabulous ending to a fabulous event.

This year’s dream team was Tom Hoenig, former Kansas City Fed president; Bill White, former chief economist at the Bank of International Settlements; and Felix Zulauf, ace money manager and longtime Barron’s roundtable member, your humble analyst, with David Bahnsen ably moderating. The summary you’re about to read doesn’t capture the actual intensity and informative value of the final panel.

The discussion quickly went to one critical question—perhaps the critical question: How hard will the Fed fight inflation? Everything hinges on it. I hope and believe Jerome Powell will keep pushing until inflation drops below 3%. I don’t know how long that will take, and I fully expect the Fed will break some things trying to get there. That’s going to hurt but a 1970s rerun would be even worse. We have no good choices left.

That led to some follow-on questions: Will the Fed keep tightening, and what if it stops too soon? Here Tom Hoenig has a lot to say because he actually sat at the FOMC table for 20 years, through multiple crises. He’s seen how those discussions go. He knows many of the players and how they think. Here was his initial answer:

“I think that the FED will push until unemployment starts to rise too sharply in their opinion. If the unemployment rate starts to rise to 5% or more, I think that they will back off.

“Now, I hope that if they find themselves in that circumstance, they will pause and not reengage in quantitative easing or lower interest rates just to get us out of the slowdown that is inevitable, given where we’re starting from with 8%‒8.5% inflation almost. And I think if you look at Powell’s spring 2019 actions, when the market threw a liquidity tantrum in the reverse repo market and so forth, his inclination will be to step in. It will take a lot of discipline on his part and on the FOMC’s part to say, ‘Wait a minute, we may pause, but we’re not going to stop. We’re going to pause in terms of raising interest rates, but we’re not going to reduce them and we’re going to have to get through this. And yes, unemployment’s going to be higher.’

“But if he doesn’t do that and he starts to back away, then we’re going to have the 1970s all over again. Start, stop, inflation goes up, then comes down, unemployment rises, therefore they back off. That’s what you want to avoid and that’s the danger going forward.”

A lot to unpack there. Tom noted the inevitable tension in the Fed’s mandate. It is supposed to pursue both price stability and full employment. The unemployment rate stands at 3.6% right now. If 5% is what the Fed considers too high, they still have room to act. (There are plenty of job openings, although this week’s ADT numbers showed small businesses significantly reducing their new hires, and some actually laying off workers.)

The Fed can put a damper on growth and see if inflation responds. That seems to be the plan right now. But if growth declines enough to create 5% unemployment, what do you think markets will be doing? It won’t be pretty. Between politicians yelling about lost jobs and investors upset about falling asset prices, the Fed will get heavy pressure to change course.

Tom Hoenig, having been there, pointed out the Fed has intermediate options. It can pause tightening without actually changing direction. That might be a reasonable choice, too. He said the danger comes if they look reactive. They can’t get into a start/stop pattern. They need to stamp out inflation first, then deal with the damage later. Whether they will do it that way remains to be seen.

Felix Zulauf was more pessimistic. He thinks the Powell Fed is quite different from the Volcker Fed, and not just because of the personalities. It’s a different situation and a different financial zeitgeist. He doesn’t think the Fed, or any other central bank can get away with imposing the kind of pain Volcker did and will stop as soon as this year.

Then Bill White, in his quiet, studious way, dropped the real bombshell.

“Back into Deflation”

David Bahnsen mentioned to Bill White that the Fed would be looking not only at unemployment and the stock market, but also the credit markets for signals. Bill agreed and noted the banks are weaker than many think. Then he said this:

“My real worry on the downside is that it may be that the fragilities are so great at the moment that a moderate degree of tightening will in fact spark a downturn of such a magnitude that even if the Fed does back off, that there’s not much that can be done about it, that will have a downward momentum… that we really won’t be able to handle.”

Whoa. During Bill White’s tenure at the BIS, he was remarkably correct in his analysis. He often went against the common narrative, one of the reasons he is my favorite central banker. He’s never shied away from telling it like it is.

We’re all (correctly) worried about inflation getting out of hand and what to do about it. Bill said, very matter-of-factly, our escape hatch may already be closed. The “fragilities” prevent us from making that soft landing. Relatively mild tightening will “solve” the inflation problem by sending the economy into deflation instead.

Bill then elaborated on what will happen when the Fed hits these fragilities. It will back off and then…

“All that does is generate another asset price boom, and another upward surge in inflation. And then eventually they have to turn to it. It is just making the underlying fundamentals worse and then things collapse and it’s even worse.

“So at this juncture, I think I’m really worried about [future] debt deflation and sooner rather than later. And I don’t think we’re prepared for it. We’re not prepared for it in terms of public psychology, and we’re not prepared for it in terms of the facilities that we’ve got, not just in the US, but perhaps more importantly, worldwide to deal with the degree of debt restructuring that’s got to come out of a deep debt deflation problem.

“We don’t have either the administrative means, or for that matter, we don’t have any principles about sovereign restructuring to guide restructuring.”

He said that so calmly, I suspect the audience wasn’t sufficiently terrified. The only thing worse than out-of-control inflation is out-of-control debt deflation, and Bill is worried about it “sooner rather than later.” That should leave you shaking in your boots. Let me explain why.

Inflation isn’t great but it has a silver lining: It favors debtors by letting them repay their loans with cheaper money. A few years of moderate inflation might have helped everyone reduce their leverage. Far better not to have accrued so much debt in the first place, but it’s where we are.

Deflation does the opposite, making debt repayment harder. That would be a guaranteed global crisis. Many overextended debtors (especially emerging market corporations with dollar-denominated debt) would be unable to pay—probably including some governments. Then what? Bill White—one of a handful on our planet who will have the answer if one exists—says we aren’t ready for it.

Yes, we have a system for individual and corporate bankruptcies. It works but slowly. Exponentially increasing its case load will be a problem. We don’t have a good system for handling sovereign defaults. Are we going to foreclose on China? Italy? Brazil? That won’t go well.

Then there’s Washington—the biggest debtor of all, when you count the obligations like Social Security and Medicare. Inflation just increases the size of the obligations for these entitlement programs. I was actually surprised to see how much my Social Security check increased last year and we haven’t even gotten into this year’s big inflation.

Fiscal Takeover

Felix Zulauf observed that already-staggering government debts will probably get bigger.

“I think monetary policy has reached the point where it is not effective anymore in stimulating the economy to a very large extent, or to the extent it used to be in the past. And therefore, we are at the point where fiscal policy takes over. What you see as a result of that is that we will run larger deficits over the next couple of years than in the past.

“You will also see that the government share of GDP will continue to rise. Yours in the US was in the low 20%. It’s now in the upper 30%. In Europe, the EU is at 54%. France is at 64%, government share of the economy. And the government is the least effective part and least productive part of the economy. In a sense, all the others, the private sector has to support that economy.

“The private sector’s percentage is shrinking while the government sector’s is growing. And that creates structural problems that eventually will be financed over the printing press in a way. That’s the way we are going, I believe.”

This is the box we’re in. Stopping inflation will create unemployment and other pain, such as falling stock markets and a potential credit crisis, to which governments will have to respond. That will add to already high and growing debts. As Felix says, government spending is both the least productive part of the economy and a growing share of the economy.

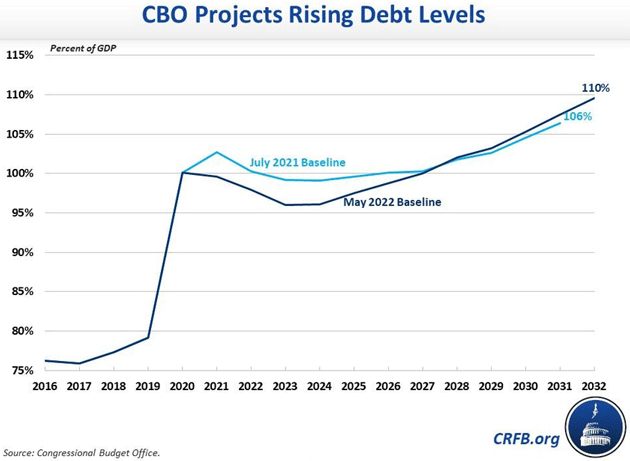

Last week the Congressional Budget Office released new debt projections, the first since July 2021. They now expect federal debt will be 110% of GDP by 2032. [Frankly, that is ludicrous. We are already at 129% according to usdebtclock.org.]

Source: CRFB

That calculation involves a bunch of assumptions, one of which is that real GDP growth will average 1.7% over the next 10 years, with no recessions. CBO also presumes PCE inflation will average 2.1%. They also assume away much of the real world. These seem like overly optimistic expectations, so there’s every reason to think reality will be far worse.

This also assumes Congress and the White House don’t aggravate the situation. That is also unlikely, no matter which party is in charge. There is no constituency for fiscal sanity in the US. The parties are simply irresponsible in different ways.

See that big jump in 2020? That was all the COVID spending, some of which helped spark the current inflation. But from the politician’s perspective, the reaction is, “Hey, we got away with it.” They’ll do it again in the next major crisis, and there’s a good chance we will have one before the 2020s end.

That’s a depressing outlook, I know. But we also know the Earth will keep rotating, and the clock won’t stop. We won’t be able to hide indefinitely. At some point, we’ll have to face these problems and resolve them. That will be what I’ve called “The Great Reset” (not the WEF version).

And to a great extent, the final panellists each saw a similar “finale” coming. They differed on some details, but none saw it being pleasant or easy.

We are going to rationalize all this: the debt, the entitlements, the other government spending, the overvalued assets, all of it. I believe part of the answer will involve rationalizing our tax system. I think we’ll have to supplement the income tax with a value-added tax. It will hurt, yes. But we as a country need to learn that government and its benefits aren’t free. If we want those services, we have to pay for them fairly and quickly, and stop passing the buck to future generations.

We’re going to learn a very hard lesson about balancing budgets. We either have to deeply cut entitlements, to which I assign 0% probability (except for tinkering around the margins), or we have to raise taxes to a point that balances the budget. That can’t be done with income and corporate taxes, though they will certainly rise. It can only be accomplished with a VAT, which will somehow have to be designed to not inflict too much pain on the bottom portion of the economy. I think this is possible, but it will only happen in the middle of a crisis of severe proportions.

And that was my closing point:

“We’re going to come to the edge of the abyss and we’re going to look over it and go, ‘Oh my God, we’re all going to die. What are we going to do?’ And then like Winston Churchill said, after we’ve tried everything else, Americans will finally do the right thing.

“It will be uncomfortable. We’re going to hate it. It’s going to be worse than castor oil, but we’ll get through it. Our lives will go on. We’ll still have family. We’re going to live longer. We’re going to be healthier. We’re going to have more cool toys. So, I don’t feel too sorry for us in the future.”

The saddest part is that the coming pain was avoidable. We had alternatives. Collectively, we didn’t choose them, and now we’ll pay the price. But we will get through it and find something better on the other side. Using George Friedman’s concept, we might call it “the Storm before the Calm.” I expect this storm in the mid- to late 2020s, leading to a boom and renewed growth in the 2030s.

And for the astute investor? There are going to be opportunities all along the way.